Picture yourself biting into something so old that its origins stretch back to when the world didn’t know sugar the way we do now. India’s relationship with dessert isn’t just about festivals—it's about roots deeper than many empires. There’s a reason ancient texts mention sweets not as treats, but as sacred, everyday things. So, what is the oldest dessert in India? The answer takes us beyond your grandma’s rasgullas or the Instagram craze of gulab jamun. It's a story baked with time, ritual, and some unexpected science.

The Dawn of Indian Sweets: How Ancient Are We Talking?

Try guessing how old Indian desserts really are. 2,000 years? Try 5,000. Archaeologists uncovered large, granitic mortars at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, suggesting people there ground grain for some kind of sweet porridge or balls, even before refined sugar existed. Imagine kheer, but with the rawest form of sweetness—honey, dates, or jaggery. Sanskrit scriptures like the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE) mention payasam, a milk-and-rice pudding drizzled with ghee or honey, offered to gods. Yes, oldest Indian dessert isn't just an ancient food—it’s practically a Vedic ritual.

Back then, sugarcane was a wild grass, not the mainstay it is now. Instead, sweets were made with natural sugars: honey, fruits, and even plant saps. The very word ‘saccharum’ (where sugar comes from) traces to Sanskrit ‘sharkara.’ Isn't it wild that the chemistry of sweets shaped international trade, drawing even the Persians to India by 500 BCE? Sugar boiled into syrup, poured over popped rice or lentil balls—that’s one step from the laddus we know.

Payasam, Ladoo, or Puran Poli—Which Came First?

The real debate: Everyone has a favorite. But when scholars look at the oldest documented sweet, the race narrows down to payasam (kheer), laddoo, and puran poli. Ancient Ayurvedic texts and temple inscriptions put payasam as a fixture in religious ceremonies, backed by mentions in Mahabharata and Ramayana (compiled 500–200 BCE). Sometimes, payasam is so old it’s served in python-shaped brass pots in southern temples, an unchanged recipe over centuries.

Laddu, too, turns up everywhere. Charaka Samhita, a legendary Ayurvedic treatise, lists sesame and jaggery balls—basically, ancient laddus—as immunity boosters. Soldiers packed them as travel rations. Puran poli, on the other hand, is a sweet, stuffed flatbread, beloved in Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh for ages, though its earliest references appear centuries after payasam. No other dessert is as thoroughly documented in India’s oldest religious rituals as kheer, making payasam arguably the front-runner for the oldest Indian dessert still made today.

When you eat these, you’re not just snacking on tradition. You're tasting history—layers of it. The oldest versions used rice, millet, or even barley, sweetened with jaggery and sometimes spiced with cardamom and saffron. It's that simple, yet that deep.

Sugarcane and the Science Behind Sweetness

Indians didn’t always have access to ‘white sugar’ as we picture it. When Alexander’s army hit India in 326 BCE, they found what they described as “honey without bees.” They took sugarcane cuttings back to Persia and Europe, changing world cuisines forever. By the Gupta era (around 335–550 CE), Indian cooks had worked out ways to purify sugar, opening possibilities for complex sweets.

Kheer—payasam—showcases this scientific leap. Early versions were all about rice, milk, and sweetening from palm sugar or honey. Over centuries, it got richer with clarified butter, nuts, raisins—each region tweaking the recipe but sticking to that creamy base. Manuscripts from the Chola and Vijayanagara empires (roughly 9th–16th century) list recipes eerily close to what’s served as prasad in temples from Varanasi to Thiruvananthapuram.

Laddus morphed from wholesome balls of sesame or wheat and jaggery—with peanuts and even roasted pulses joining the mix as sugar became more affordable in common homes. Regional varieties flourished: boondi laddu for North India’s festivals, rava laddu for South Indian temple kitchens. Ancient cooks weren’t just making food—they were feeding armies, curing ills, and marking milestones, all through dessert.

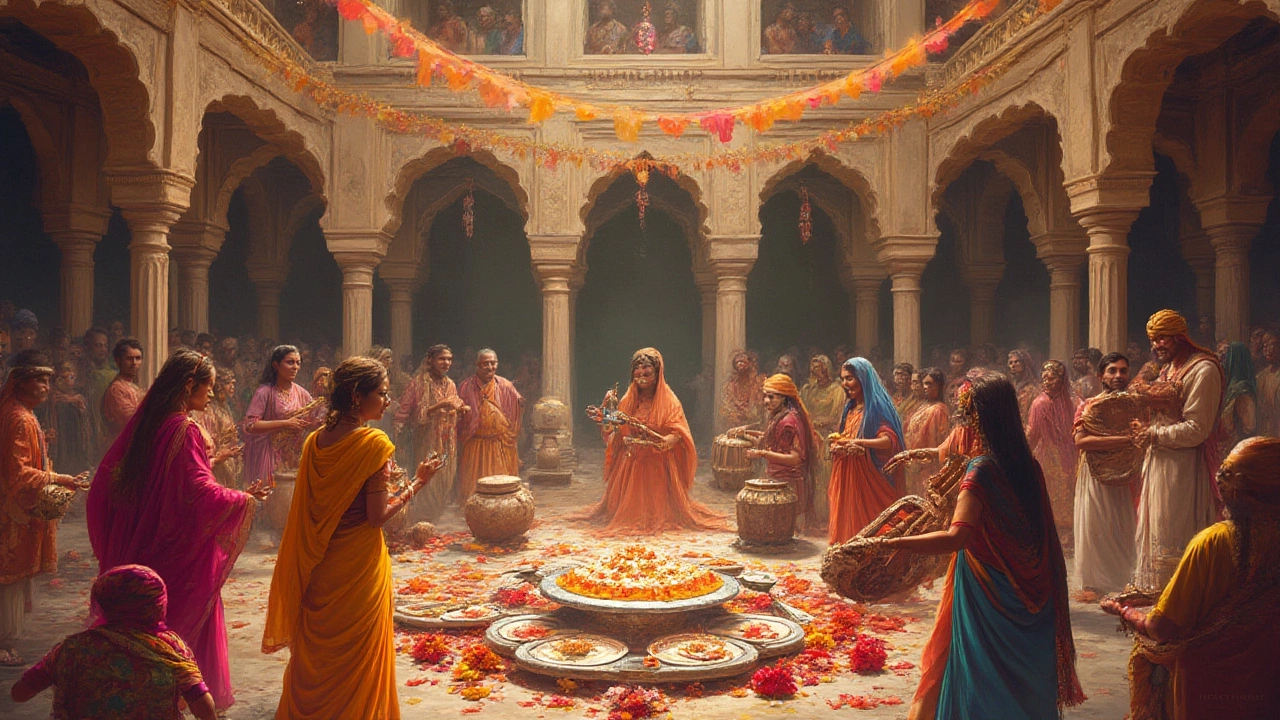

Cultural Secrets: Rituals, Traditions, and Sweet Offerings

Food is never just food in India. Desserts like payasam or laddu are at the heart of everything sacred. In Kerala’s famous Guruvayur temple, payasam is offered in golden pots daily as part of a 1,400-year-old tradition. Laddus reign at Tirupati’s Venkateswara temple, which produces around 300,000 laddus for pilgrims every day—each stamped and sacred, based on recipes kept secret for centuries.

On the Ganges’ banks, you’ll still see priests making ancient rice puddings for river deities. But these recipes weren’t written like modern cookbooks. Knowledge passed from temple cooks to apprentices, recited along with prayers, encrypted in stories. Even the order of ingredients follows religious symbolism—milk for purity, rice for prosperity, ghee for good fortune. Sweets mark births, marriages, and everything in between.

What’s even cooler? Some tribes in Chhattisgarh and Odisha still make primitive forms of rice cakes using wild honey, echoing ancient pre-sugar traditions. In family kitchens, grandmothers blend tradition and innovation: jaggery for nostalgia, condensed milk for speed, all served with stories about how their own grandmothers measured rice by hand.

Tips for Tasting (And Making) India’s Oldest Desserts

Craving a taste of actual history? Start with payasam or laddoo—their simplicity is their secret. Use short-grain rice for a creamy texture if you make payasam at home. Try swapping sugar for jaggery or palm sugar, which brings extra depth and links you straight to those ancient kitchens. Roasting rice or wheat before simmering in milk unlocks a toasted, nutty richness, a trick temples still use.

If you want to go older, reach for barley or millet instead of rice in your kheer. Sweeten with date syrup or honey, and keep the spices gentle—maybe just a pinch of cardamom. Even the classic puran poli gets richer with time: fresh ghee and homemade chana dal paste are key.

On holiday or at a temple, don’t skip prasad—chances are, that bowl of kheer is almost exactly what ancient cooks prepared for the gods. Watch for regional twists: In Andhra Pradesh, kheer (paramannam) swaps in jaggery, while North India’s phirni uses ground rice for a soft pudding texture.

Here’s a table to help you spot the timeline and ingredients of these heritage sweets:

| Dessert | Ancient Name | Common Ingredients | First Recorded Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payasam/Kheer | Payasa, Ksheerannam | Milk, rice/millet, honey/jaggery | c. 1500 BCE (Rigveda) |

| Laddoo | Ladduka, Modaka | Sesame, wheat, jaggery, ghee | c. 300 BCE (Charaka Samhita) |

| Puran Poli | Obbattu, Holige | Wheat flour, chana dal, jaggery | c. 600 CE (later Puranic texts) |

Most importantly: savor the bite knowing you’re tasting not just food but millennia of Indian memories, rituals, and kitchen secrets. The country’s oldest dessert isn’t a fixed recipe but a living story, still unfolding, one sweet mouthful at a time.