Indian Goodbye Expressions Comparison Tool

Discover how different goodbye expressions work in Indian culture. This tool helps you understand when to use "Tata," "Phir milenge," and other phrases depending on context.

Filter by Context

Tata

The most common casual goodbye in India, especially at street food stalls. Short, warm, and efficient for quick interactions.

Why it works: It's not too formal, not too abrupt. Perfect for busy street food environments where time matters.

Phir Milenge

Means "We'll meet again." More formal than "Tata" but less formal than "Alvida." Common in offices and with elders.

Why it works: Conveys continuity and relationship without being overly emotional.

Alvida

The formal Hindi word for goodbye. Sounds too stiff for casual street interactions but appropriate in formal settings.

Why it works: More appropriate for business settings than street food interactions.

Namaste

Traditionally used as both greeting and farewell. Common in South India and with elders. More spiritual connotation.

Why it works: Works as both hello and goodbye, especially with older people.

Bye

Commonly used by younger Indians and in international contexts. Feels foreign in traditional street food settings.

Why it works: Used in cities but sounds too formal for street food environments.

Povvu (Telugu)

Telugu word for goodbye. Used in South India, especially among Telugu speakers. Less common in street food contexts.

Why it works: Regional expression that's less widely understood outside Telugu-speaking communities.

Why "Tata" Dominates Street Food Culture

"Tata" works perfectly in street food environments because it's quick, warm, and practical. Unlike "Bye," it carries a soft, musical quality that fits the rhythm of busy street life. It's not too formal or emotional, which is perfect for transactions that happen in seconds rather than minutes.

As the article explains, "Tata" is like the clink of a glass tumbler or the hiss of a samosa frying—simple, familiar, and perfectly suited to the moment.

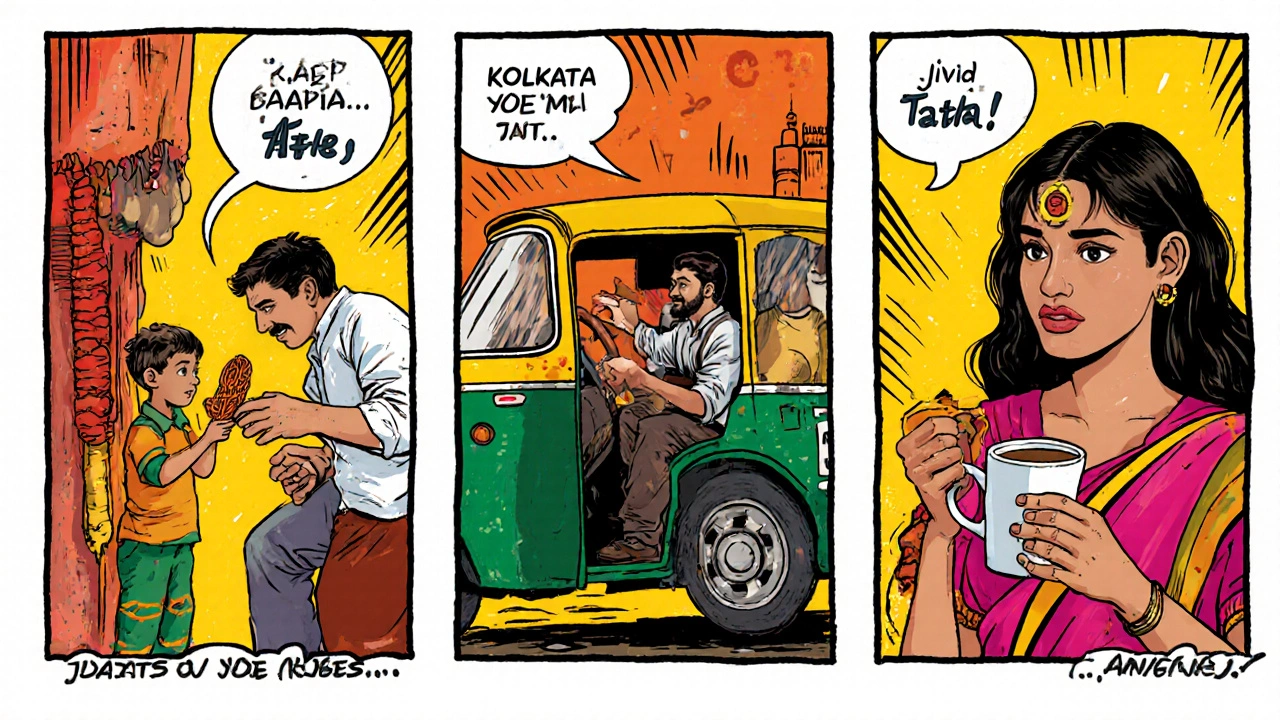

Walk into any busy street food stall in Mumbai, Delhi, or Kolkata, and you’ll hear it over and over: Tata. Not ‘bye.’ Not ‘see you later.’ Just ‘Tata.’ It’s quick, it’s casual, and it’s everywhere. If you’ve ever stood in line for a piping hot samosa or a glass of sweet lassi, you’ve probably heard it. But why? Why do Indians say ‘Tata’ instead of ‘bye’? It’s not just slang-it’s a cultural habit woven into the rhythm of daily life, especially around food.

The Sound of a Quick Goodbye

- You order your pav bhaji from the vendor who’s been serving the same corner for 20 years.

- He hands you the plate, slightly greasy, with a side of extra chutney.

- You say ‘Thank you.’ He smiles.

- You turn to leave. He says, ‘Tata.’

‘Tata’ isn’t even Indian in origin. It’s borrowed from English. But here’s the twist: it didn’t come from formal British colonial speech. It came from the way British nannies and servants used to say ‘Tata bye-bye’ to children. Over time, ‘bye-bye’ got dropped, and ‘Tata’ stuck. It was cute, short, and easy to say. And in a country where speed matters-especially when you’re juggling a plate of chaat, a bus schedule, and a screaming toddler-it became the perfect farewell.

Why ‘Tata’ Thrives in Street Food Culture

Street food in India isn’t just about eating. It’s about connection. It’s about the vendor who remembers your name, the guy who always adds an extra chili, the aunty who gives you a free piece of jalebi because you come every Tuesday. These aren’t transactions. They’re tiny rituals.‘Tata’ fits perfectly into that rhythm. It’s not a formal ending. It’s a pause. A soft punctuation mark between one interaction and the next. You don’t need to say ‘Have a nice day’ or ‘Take care.’ That would take too long. You’re standing on a sidewalk, maybe juggling three things in your hands, and the next customer is already waiting. ‘Tata’ is the polite, efficient way to close the loop.

Compare it to other cultures. In Japan, people bow. In Italy, they kiss cheeks. In India, especially in street food settings, they say ‘Tata.’ It’s the cultural equivalent of a nod. No drama. No fuss. Just a quick, warm exit.

It’s Not Just About Food

You’ll hear ‘Tata’ in rickshaws, at bus stops, in small shops, even in family homes. But it’s most alive where people move fast and talk fast-like street food zones. Why? Because the environment demands it.Think about the rhythm of a Delhi street food market at 7 p.m. The sizzle of oil, the clatter of steel plates, the shouts of ‘Pani puri!’ and ‘Masala chai!’ People are rushing between stalls, grabbing food to eat on the go. There’s no time for long goodbyes. ‘Tata’ is the linguistic equivalent of a high-five-quick, friendly, and unmistakable.

Even kids learn it early. My cousin’s 5-year-old daughter in Jaipur says ‘Tata’ to her auntie who sells kachori at the temple gate. She doesn’t know it’s borrowed from English. To her, it’s just how you say goodbye after getting your snack.

Other Ways Indians Say Goodbye

‘Tata’ isn’t the only option. But it’s the most universal in casual, urban settings. Here’s what else you might hear:- Phir milenge - ‘We’ll meet again.’ Common in Hindi-speaking areas. Sounds more formal, often used in offices or with elders.

- Alvida - The formal Hindi word for goodbye. Rarely used in street settings. Sounds like a news anchor saying it.

- Namaste - Sometimes used as both hello and goodbye. Especially in South India or with older people.

- Bye - Used too, especially by younger people or in cities. But it feels foreign. Like wearing a suit to a street food stall.

‘Tata’ wins because it’s not trying to be anything. It’s not trying to be Indian. It’s not trying to be British. It’s just… there. Like the smell of cumin in hot oil. You don’t question it. You just accept it.

The Hidden Meaning Behind ‘Tata’

There’s something deeper here. ‘Tata’ carries warmth without weight. It doesn’t ask for emotion. It doesn’t demand a response beyond a smile. In a country where relationships are often layered with obligation-family duties, social expectations, caste ties-‘Tata’ is a rare moment of freedom.You don’t have to feel guilty for leaving. You don’t have to promise to come back. You don’t have to explain why you’re in a hurry. You just say ‘Tata,’ and the vendor says it back. And that’s enough. It’s a silent agreement: we’ve shared something small, and it was good. Now, go on.

That’s why it survives. In a world full of digital notifications, long goodbyes on Zoom, and over-analyzed social interactions, ‘Tata’ is a quiet rebellion. It’s simple. It’s human. It’s real.

Why You’ll Never Hear ‘Bye’ on a Street Food Stall

Try saying ‘Bye’ to your chai wallah. He’ll probably smile and say ‘Tata’ back. Not because he’s correcting you. But because ‘bye’ feels too final. Too cold. Too English.‘Bye’ comes from ‘goodbye,’ which itself comes from ‘God be with ye.’ It’s loaded with history, religion, and weight. ‘Tata’ has none of that. It’s just a sound. A friendly noise. Like the clink of a glass tumbler or the hiss of a samosa frying.

In India, even small words carry meaning. ‘Tata’ doesn’t just end a conversation. It honors it.

What This Says About Indian Culture

The use of ‘Tata’ isn’t random. It’s a reflection of how Indians navigate daily life: fast, warm, and deeply practical. You don’t need to over-explain. You don’t need to perform emotion. You just need to be present.Street food is the perfect stage for this. It’s where class, language, and culture blend. A college student in Delhi, a truck driver in Punjab, a grandmother in Chennai-they all say ‘Tata.’ It’s one of the few things that cuts across every boundary.

It’s also a sign of how India absorbs the world and makes it its own. ‘Tata’ didn’t come from tradition. It came from colonial contact. But it didn’t stay foreign. It got adapted. It got softened. It got Indianized.

That’s the magic of Indian culture. It doesn’t reject outside influences. It takes them, reshapes them, and gives them new life.

So Next Time You Hear ‘Tata’

Don’t think of it as a mistake. Don’t think of it as broken English. Think of it as a cultural fingerprint. A tiny, beautiful piece of everyday India.Next time you’re at a street food stall, say ‘Tata’ back. Not because you have to. But because you want to. Because you’ve shared something real. And in a world that’s getting louder, sometimes the quietest goodbyes are the ones that stick.

Is ‘Tata’ used only in North India?

No. While ‘Tata’ is most common in North and West India, you’ll hear it in Chennai, Bangalore, and even in small towns in Odisha. It’s become a nationwide casual farewell, especially in urban and semi-urban areas. In South India, you might also hear ‘Povvu’ in Telugu or ‘Po’ in Tamil, but ‘Tata’ is still widely understood and often used by younger people, especially around street food.

Do older Indians say ‘Tata’ too?

Yes, but less often. Older generations tend to use ‘Namaste’ or ‘Phir milenge.’ But even grandparents in cities like Delhi or Mumbai will say ‘Tata’ to their grandchildren after handing them a snack. It’s one of the few words that crosses age gaps effortlessly. In fact, many older people say it without even realizing it’s borrowed from English.

Is ‘Tata’ considered rude if used in formal settings?

It can be. You wouldn’t say ‘Tata’ to your boss after a meeting or to a priest at a temple. In formal contexts, ‘Namaste,’ ‘Alvida,’ or even ‘Goodbye’ is preferred. But in casual, everyday spaces-like street food stalls, auto-rickshaws, or neighborhood shops-it’s perfectly normal and even expected.

Why don’t Indians just say ‘Bye’ if they know English?

Because ‘Bye’ feels too abrupt and impersonal. ‘Tata’ has a rhythm to it-it’s soft, almost musical. It sounds like a sigh of relief after a good meal. ‘Bye’ sounds like a door closing. ‘Tata’ sounds like a door gently shut, with a promise that you’ll open it again tomorrow.

Do Indians say ‘Tata’ when leaving their own homes?

Sometimes, but not always. In many homes, especially in cities, kids say ‘Tata’ to parents when leaving for school. But in more traditional households, people say ‘Namaste’ or ‘Jai Shri Krishna.’ It depends on the family. But even in homes, ‘Tata’ is growing-especially among younger generations who’ve grown up watching Bollywood and listening to pop music.

There’s no grand history behind ‘Tata.’ No ancient text. No royal decree. Just a hundred million small moments-people handing over food, smiling, and saying goodbye in the most human way possible.